The 'Brain Drain' Protocol: How to Extract IP Assets Before Your Engineers Quit

- Tim Bright

- Dec 27, 2025

- 5 min read

Why Most Invention Disclosures Never Become Patents

Here's an uncomfortable truth that patent practitioners won't tell you: most invention disclosures never make it to filed applications. Not because the technology lacks merit, but because the documentation fails to provide what patent counsel actually needs to build a defensible patent application.

After reviewing hundreds of disclosures across artificial intelligence, machine learning, robotics, and semiconductor technologies, patterns emerge. The fundamental problem isn't technical—it's structural. Engineers document what they've created the way they'd explain it to colleagues: context-heavy, assumption-laden, and focused on what's intellectually interesting rather than what's legally defensible.

Your patent counsel needs something different entirely.

What Patent Practitioners Actually Need From You

Patent counsel must satisfy four statutory requirements with your disclosure. Understanding these requirements at the disclosure stage—before significant legal fees accumulate—enables strategic decisions about which innovations warrant patent protection and how to structure that protection.

Utility is usually straightforward for technology companies. Your AI patents solve specific problems. Your semiconductor process reduces power consumption. Your robotics system improves warehouse efficiency. Document the practical application clearly.

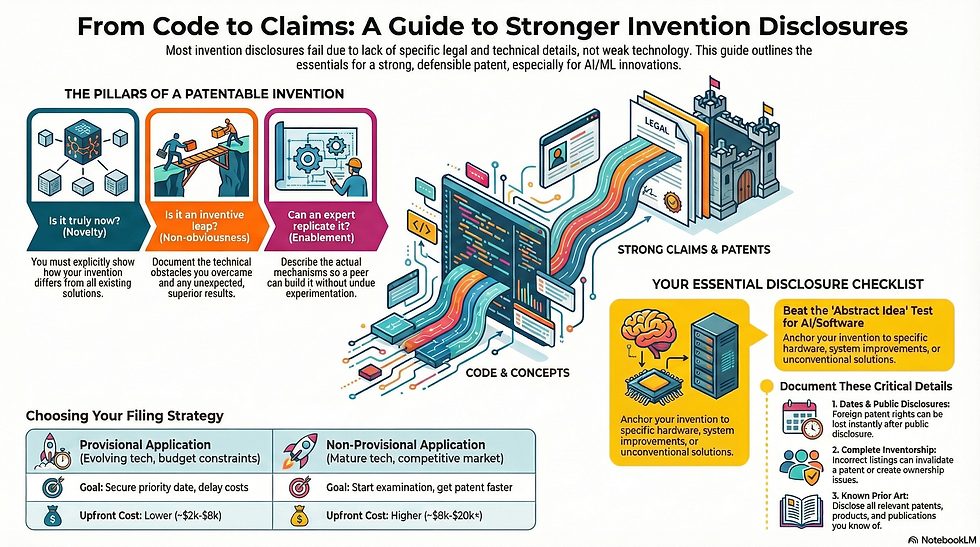

Novelty requires showing that no single prior art reference discloses every element of your invention. The critical detail: explicitly identify what distinguishes your approach from existing solutions. Don't assume your practitioner knows the field—spell out the differences.

Non-obviousness is where most applications succeed or fail. Your invention must not be an obvious combination of prior art to a person of ordinary skill in the field. Document the technical obstacles you overcame, unexpected results, and why the solution would not have been obvious given the state of the art.

Written Description and Enablement are the hidden landmines. Your disclosure must enable a person of ordinary skill to make and use the invention without undue experimentation. For software patents, neural networks, and generative AI, this means describing actual mechanisms—not just functional outcomes.

The Section 101 Challenge for AI and Software Innovation

The Supreme Court's decision in Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank created a test that has invalidated countless software patents. Understanding this framework is essential if you're pursuing machine learning patents. The test asks two questions:

Are your claims directed to an abstract idea? For AI, this is the danger zone. Claims that merely recite "collecting data," "training a model," and "outputting results" are vulnerable.

If directed to an abstract idea, do the claims include an inventive concept that transforms the abstract idea into something patent-eligible? Generic computer implementation isn't enough.

Your disclosure must emphasize:

Specific technical improvements to computer performance, processing speed, or system architecture

Unconventional solutions that go beyond the routine application of known methods

Concrete technological anchoring—tie your AI to specific hardware, sensors, or physical systems

This last point matters enormously. An ML model for "optimizing schedules" is abstract. An ML model that "processes real-time sensor data from autonomous robotic systems to dynamically adjust warehouse routing while minimizing collision probability" anchors the same core innovation in concrete technical implementation.

Essential Details You're Probably Forgetting

Dates and Public Disclosures: Under the U.S. first-to-file system, timing is critical. Document when you conceived the invention, any public presentations or publications, and planned disclosure events. The U.S. provides a one-year grace period after public disclosure, but most foreign jurisdictions offer no grace period. A conference presentation you forgot to mention can permanently destroy your international patent rights.

Complete Inventorship Information: Inventorship is a legal determination based on contribution to conception—not effort, seniority, or lab participation. Document specifically who conceived each technical element and when. Incorrect inventorship can invalidate patents; conversely, omitting actual inventors means they retain ownership interests, creating nightmare scenarios where patents become co-owned with competitor employees.

Known Prior Art: List every potentially relevant patent, publication, product, or project known to your team. Include brief explanations of how your invention differs. Your counsel will assess which references require USPTO disclosure, but that assessment requires first knowing what references exist.

Technical Implementation Details: This is where engineers and patent pros diverge. You know your system; your counsel doesn't. Include:

System architecture diagrams showing component relationships

Flowcharts depicting algorithmic steps and decision points

Parameter ranges and operational thresholds

Pseudocode or functional descriptions of computational processes

Alternative embodiments and variations

The Provisional vs. Non-Provisional Decision

The choice between provisional and non-provisional applications involves tradeoffs between cost, timing, and technical certainty that vary depending on your technology maturity and market timeline.

Provisional applications establish priority dates at a lower cost ($2,000-$8,000 preparation fees) and buy 12 months to refine technology before committing to expensive non-provisional prosecution. They enable "patent pending" status for fundraising without full investment. However, they create timing pressure: the 12-month deadline is absolute. Miss it, and you lose the priority date.

Non-provisional applications enter examination immediately ($8,000-$20,000+ preparation fees) and move toward potential grant in 12-18 months with expedited examination. For companies in fast-moving competitive landscapes, this acceleration matters.

Choose provisional filing if:

Technology is still evolving but core innovation is solid

You have 12+ months before product launch

Budget constraints require deferring major legal expenses

International expansion is uncertain

Choose non-provisional filing if:

Implementation is complete and stable

Competitors may file similar innovations soon

You need enforceable rights for commercial purposes

Investor due diligence requires pending patent applications

AI/ML Invention Disclosure: A Practical Framework

AI and machine learning inventions require special attention to survive patent examination. Structure your disclosure around these elements:

Technical Problem Definition: What specific technical problem does the invention solve? Why couldn't existing AI approaches solve this? What technical limitations did prior approaches encounter?

Model Architecture: Describe the architecture in detail—layers, connections, novel structures. Include diagrams showing component relationships. Specify any novel loss functions, activation functions, or training procedures. This satisfies both written description requirements and enables your practitioner to draft claims grounded in concrete implementation.

Training Methodology: Document the training process: data sources, preprocessing steps, optimization algorithms, learning rate schedules, regularization techniques, and convergence criteria. For neural networks, specify network architecture. For generative AI, detail the generation process.

Performance and Results: Provide quantitative improvements over baseline approaches. Specific metrics demonstrating technical advancement strengthen your §101 position. Include comparative data, ablation studies showing which components contribute to performance, and explanations of why architectural choices enable observed improvements.

Integration and Application: For robotics or semiconductor applications, document how AI components control systems. This integration often provides the inventive concept that survives examination.

Moving Forward: From Disclosure to Patent

A well-prepared invention disclosure doesn't just speed up filing—it produces stronger patents. When your counsel focuses on claim strategy rather than chasing down missing information, the resulting application better protects your competitive position.

For startups and independent inventors, the investment in thorough documentation at this stage pays dividends throughout your patent's lifecycle: more efficient prosecution, stronger positions against examiner rejections, and defensible claims if your patent is ever challenged.

In competitive fields like artificial intelligence, semiconductor manufacturing, and robotics, intellectual property increasingly determines market leadership. The quality of your invention disclosure becomes a competitive advantage—the difference between enforceable patents that support licensing revenues and valuations, versus innovations that pass into the public domain or face enforcement actions from competitors who filed first.

Begin with a candid assessment: Can someone skilled in your field—a competitor with product knowledge but no access to your team—implement your invention from your disclosure alone? If not, you have work to do. But that work, completed before filing, prevents expensive revisions later and builds IP protection that actually matters when your business needs it most.

About Bright-Line IP

We provide patent prosecution and strategic intellectual property counsel for artificial intelligence, machine learning, robotics, and semiconductor innovations. Our practice helps technical founders build patent portfolios optimized for venture capital due diligence and exit transactions. We specialize in freedom to operate analysis, patent strategy optimization, startup IP development, and IP due diligence preparation.

Schedule a consultation at brightlineip.com.

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Intellectual property strategy and patent decisions should be developed in consultation with qualified counsel familiar with your specific technology and business circumstances.

Comments