Mapping the 'White Space': How to Find the Open Lane in a Crowded Tech Stack

- Tim Bright

- Dec 27, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Dec 31

The Reality Most Founders Don't Understand

When you ask a technical founder "Is my innovation patentable?"—you've asked the wrong question. The real question is: "What competitive position does my innovation occupy in the existing technology landscape, and how should that shape my patent strategy, product development roadmap, and IP investment decisions?"

This distinction separates the founders who build valuable patent portfolios from those who accumulate useless papers.

What Prior Art Really Is

Prior art encompasses any publicly available information that existed before your patent application's effective filing date. This includes granted patents, published patent applications, academic papers, conference presentations, open-source code repositories, product manuals, and technical standards. A USPTO examiner will deploy prior art to answer two fundamental questions: Does a single reference disclose all elements of your claimed invention (novelty)? Would a person of ordinary skill combine multiple references to arrive at your invention (obviousness)?

The scope here is critical. Prior art is not limited to traditional patent literature. A machine learning technique thoroughly documented in academic papers two years before your filing date—prior art. A semiconductor process disclosed in an IEEE standard—prior art. A competitor's product demonstrating the technology—prior art. A GitHub commit, a blog post, a trade show demonstration—all potentially prior art.

Patent Literature Versus Non-Patent Literature: Why Examiners Have Unfair Advantages

Most founders focus their prior art searching on patents. This is rational—patents are organized, indexed, and searchable. This is also strategically dangerous.

The hidden threat: Non-patent literature (NPL) is where examiners find the references that blindside applicants. In AI, robotics, and semiconductor innovation, academic publications often precede commercial patent filings by 18–36 months. A generative AI technique that feels novel in the patent landscape may be thoroughly documented in arXiv preprints. A robotics architecture may be disclosed in IEEE conference proceedings years before the first patent application.

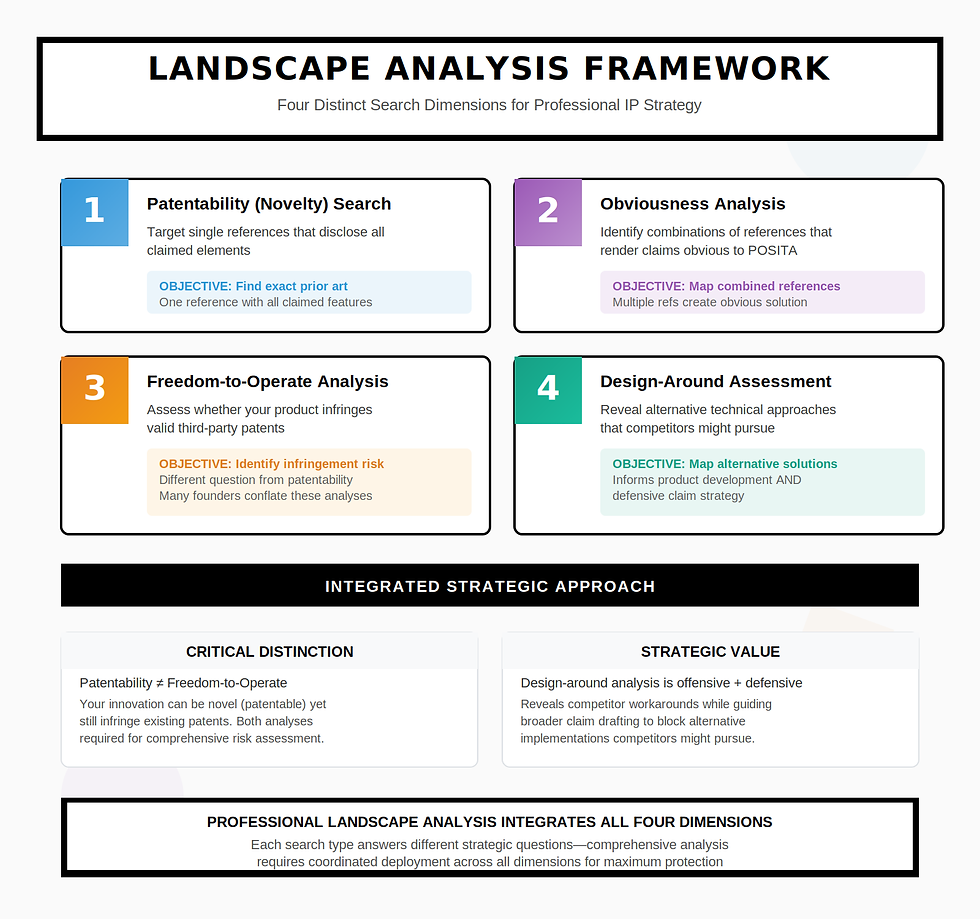

Professional landscape analysis integrates four distinct search dimensions:

Patentability (Novelty) Searches target single references that disclose all claimed elements.

Obviousness Analysis identifies combinations of references that render claims obvious to a person of ordinary skill.

Freedom-to-Operate (FTO) Analysis assesses whether your product infringes valid third-party patents—a different question from patentability that many founders conflate.

Design-Around Assessment reveals alternative technical approaches that competitors might pursue, informing both your product development and your defensive claim strategy.

Each search type answers a distinct business question. A founder asking "Can I patent this?" needs patentability analysis. An investor asking "Will my product launch create litigation exposure?" needs FTO analysis. An R&D team asking "Where should we invest next?" needs white space and competitive landscape mapping.

Why Google Patents Isn't Enough

Google Patents is free, accessible, and genuinely useful for initial reconnaissance. This is sufficient for a quick sanity check. It is insufficient for the analysis that actually matters—systematic landscape assessment across multiple search methodologies. For strategic decision-making, it is dangerously incomplete.

Classification code searching (the Cooperative Patent Classification system that organizes patents by technical domain) is primitive in Google Patents. Professional databases like PatSnap, Derwent Innovation, and Orbit provide hierarchical searching that identifies conceptually related patents using standardized taxonomy. Citation analysis is superficial in Google Patents; professional platforms reveal technological lineages, showing which foundational patents influenced subsequent innovation and which competitors are building upon.

Foreign language patents are poorly served. In semiconductor and AI innovation, substantial prior art originates from Chinese, Japanese, and Korean filings. Google Patents' translation and coverage for these jurisdictions is inconsistent.

Interpreting Search Results Without a Law Degree

The goal of landscape analysis is not generating a frightening list of references. It is developing nuanced understanding of how your innovation relates to existing technology.

Focus on the claims, not the specification. When evaluating patents for freedom-to-operate purposes, the specification does not define protection scope—the claims do. A patent might describe your entire technology in its background section while claiming something completely different. Read independent claims first, then dependent claims that narrow them.

Assess element-by-element coverage. Anticipation requires that a single reference disclose every claim limitation. If even one element is missing, that reference does not anticipate—though it may contribute to an obviousness rejection when combined with others.

Identify your point of novelty. What makes your innovation different? Prior art analysis should clarify where genuine innovation resides—often different from what the inventor initially assumed.

Evaluate commercial relevance. Not all prior art creates equal risk. A blocking patent held by a well-funded competitor creates different strategic considerations than one held by a non-practicing entity or in an abandoned application.

Red Flags That Demand Immediate Strategic Adjustment

Certain search findings require immediate repositioning:

Direct anticipation of core claims means your intended claims cannot be obtained as drafted. Narrow claims to capture genuine novelty or explore continuation opportunities for different aspects.

Dense patent family with active continuation practice in your technology area signals that competitors can file new claims targeting your specific product. This is common in crowded spaces like AI inference optimization.

Standard-essential patents (SEPs) indicate technology implementing industry standards (5G, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth). Your own patent position may not prevent FRAND licensing obligations.

Patent thicket with aggressive enforcer requires either designing around the portfolio, budgeting for licensing, or accepting litigation risk.

Your own prior public disclosure triggers the one-year grace period in the U.S. Any public disclosure before filing destroys absolute novelty in many jurisdictions outside the U.S.

Leveraging Landscape Analysis for Claim Strategy

Comprehensive prior art analysis conducted before filing informs two specific prosecution decisions: claim scope positioning and prosecution timing.

The closest prior art defines defensible claim boundaries. Claims must be broad enough to capture commercially valuable embodiments but narrow enough to distinguish from prior art. This calibration improves procurement velocity—the ability to move from concept to granted patent with minimum friction.

Technology clustering analysis reveals not just where competitors have filed, but where they have not. These white space opportunities represent areas for broader claims with reduced prosecution friction. In rapidly evolving sectors like generative AI, white space windows open and close quickly.

The Strategic Imperative

For independent inventors and startup founders operating with constrained resources, the question becomes: Is comprehensive landscape analysis justified at the pre-seed or seed stage?

Our perspective, informed by over a decade of prosecution experience: systematic prior art analysis is not a cost center—it is strategic infrastructure. Applications filed without landscape understanding often result in patents narrower than necessary, broader than defensible, or misaligned with actual competitive differentiation. These deficiencies compound as portfolios grow and licensing or enforcement opportunities emerge.

The founders who build valuable patent portfolios are those who treat prior art searching not as a checkbox exercise but as the foundation of informed IP strategy. They understand that the goal is not merely obtaining patents, but obtaining the right patents—claims that protect genuine innovation, withstand validity challenges, and create sustainable competitive advantage.

In the patent game, information is leverage. Landscape analysis is how you acquire it.

About Bright-Line IP

We provide patent prosecution and strategic intellectual property counsel for artificial intelligence, machine learning, robotics, and semiconductor innovations. Our practice helps technical founders build patent portfolios optimized for venture capital due diligence and exit transactions. We specialize in freedom to operate due diligence, patent strategy optimization, startup IP development, and IP due diligence preparation.

Schedule a consultation at brightlineip.com.

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Intellectual property strategy and patent decisions should be developed in consultation with qualified counsel familiar with your specific technology and business circumstances.

Comments